About 27,000 years ago, Britain was connected to Europe by a land bridge, though much of the country was covered in ice. Over time, the ice started to melt, plants recolonised and animals moved across the land bridge into Britain.

The last cold spell ended 11,700 years ago. As the ice melted, sea levels rose and Britain became separated from Europe. The plants, animals and other organisms present at this time are considered our native species. This includes the Eurasian lynx.

There are two types of evidence for the presence of lynx in Britian. There’s physical evidence, such as bones. But there’s also cultural evidence, with mentions of lynx in books and poems. It’s hard to be sure when the last lynx was lost – bones have been discovered from around 500 AD, but cultural evidence mentions lynx as late as the 18th century.

The last Ice Age to the arrival of the Romans (1st century AD)

Lynx bones have been found in caves across Britain. Scientists have been able to study these bones to find out when these lynx lived and died. Evidence dating from this time period includes:

- Lynx bones from 9000 BC found in Dog Hole Fissure, Derbyshire

- Lynx bones from 8000 BC found in Kitley Shelter Cave, Devon

- Lynx footprints dating back to 9600 – 4000 BC found on the Sefton coast, Merseyside

A lynx mandible (date unknown) from Kent's Bank Cavern, Cumbria (on display at the Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness) © Dave Wilkinson

The 1st to the 11th century

When the Romans arrived in Britain, lynx were present in northern England and Scotland. There is physical evidence to show they still lived here. This includes:

- A lynx tibia from 120 – 322 AD found in Moughton Fell Cave, North Yorkshire

- A male lynx’s skull from 77 – 530 AD found in Reindeer Cave, Sutherland

- A lynx femur from 432 – 580 AD found in Kinsey Cave, Yorkshire. This is currently the last physical evidence of lynx living in Britain

But lynx still show up in cultural evidence later in this time period, such as:

- A poem called ‘Y Gododdin’ about the ‘Battle of Catraeth’, fought in the Scottish borders around 600 AD. A version of this poem is preserved in the ‘Book of Aneirin’ from around 1275 AD. The poem commemorates some of those who died and mentions a hunter chasing animals, such as lynx, in north England or Wales

- The ‘Poetic Life of St Cuthbert’, which was written in Northumbria around 705 – 720 AD and mentions ‘cat’ in the landscape

- The Kildonnan cross slab from the Isle of Eigg, Scotland, which is a hunting scene on stone dating back to 800 AD

The 11th to the 17th century

It is most likely that we lost lynx from Britain during the medieval time period (1066 – 1485), due to habitat changes and hunting. We have cultural evidence of lynx living in Britain at this time, but so far no physical evidence has been linked to this time period. Scientists are still looking, so more lynx bones might be discovered in the future.

Cultural evidence from this time includes:

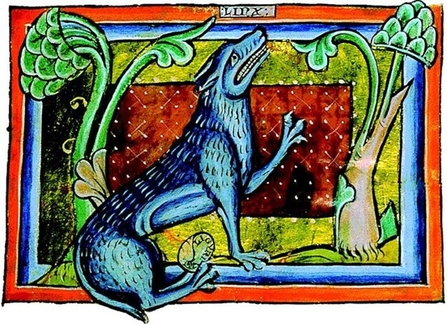

- An illustration in a bestiary (a collection of short descriptions of animals) from around 1275, which shows a lynx urinating. The urine turns to the mythical gemstone lyngurium.

- In 1587, English clergyman, William Harrison describes how there had been 'very many lions' in northern Scotland - but no longer at their time of writing, printed in later editions of Conrad Gessner's Latin Historiae Animalium (Gessner 1602: 683).

- A 1658 Letter by Topsell (1658: 382) ‘There are linxes in Divers Countries, as in the forenamed Russia, Lituania, Polonia, Hundary, Germany, Scotland.’

The illustration from the bestiary, showing lynx urine turning into the mythical stone lyngurium © The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Re-used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence.

The 18th to the 19th century

Experts generally agree that lynx were lost from Britain by this time, though they lived on in our cultural memory. Some records hint at lynx still being present, but old documents can be hard to interpret.

A 1760 record from a traveller, Richard Pocoke, suggests that a breeding population of large wild cats was in the vicinity of Auchencairn in historical Kirkcudbrightshire, southwest Scotland.

“They have also a wild cat three times as big as the common cat, as the pollcat is less. They are of a yellow red colour, their breasts and sides white.”

It is possible for a few individuals to cling on in remote places as populations fade. Could this have been a lynx?

In this time period, lynx started to disappear across Europe too. They faced the same issues of habitat loss and hunting, as well as a decrease in prey.

Discover more about lynx in Europe

The future of lynx in Britain

Lynx were lost due to the actions of our ancestors, but we can undo that damage and bring lynx back. The Missing Lynx Project is examining that possibility.

Computer models tested whether lynx populations could live in Britain. We found that lynx released in the north of England would be able to grow into a healthy population, which would span across northern England and into southern Scotland.